Identity crime has existed since ancient times. Numerous cases took place in Greece, Persia and the Roman Empire, where impostors assumed false identities to achieve political or financial gain. In the sixth century BC, an imposter assumed the identity of the brother of the shah, Smerdis, who had already been killed. He ruled for several months before being discovered and removed from the throne.1 In the Roman Empire, after the death of Emperor Nero, several imposters tried to assume his identity before being discovered and executed.2 When the Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 was introduced in the United States, college students started to acquire fraudulent identification documents (IDs) to establish that they were 21 years of age or older.3 In this case, they committed identity crimes to obtain goods and services illegally, not for financial gain.

A subset of identity crime, synthetic identity fraud (SIF), has recently emerged. SIF occurs when the identity itself does not exist and is manufactured using fake documents. The growth of SIF is closely related to pressures on financial enterprises to fight increasing competition, improve their bottom lines and address the increased use of online service delivery.

One approach to detecting SIF in online credit applications proposes analyzing the behavior of an identity on social media to gauge whether their behavior is consistent with a person’s activities in the real world. The premise behind such analysis is that while a fake account is quite easy to create, an associated digital footprint going back years is not. Thus, an extensive presence on social media with only a recent footprint can be considered suspicious and require deeper investigation.

A key component of the proposed approach is the use of a Risk Score Calculator (RSC). The RSC provides the practical means by which a financial organization can determine whether online credit applications require a review by an officer or can be approved automatically, based on a set of predefined rules.

Real Identity Fraud vs. SIF

There are two types of identity fraud: real and synthetic.4 Real identity fraud (RIF) occurs when fraudsters obtain information about actual people that allows them access to certain services without any knowledge of the person whose identity is being used. Initially, it is difficult to commit RIF because fraudsters need access to a real person’s information, which takes a certain amount of effort and is costly to scale. However, once this information is obtained, it becomes easier to use because when it is checked against existing verification mechanisms such as government databases and credit agencies, it is likely to pass scrutiny.5

SIF occurs when the identity itself does not exist and is manufactured using fake documents. In contrast to RIF, SIF is easier to perpetrate but more challenging to use for criminal purposes.6 By definition, SIF requires only some real information; the rest is fabricated. Thus, assembling all the necessary pieces of information to obtain credit, for example, requires less effort. However, difficulties arise when the synthetic identity is introduced into the financial system. Because this information is absent from any government or other database, it may be identified as problematic. Despite these challenges, SIF is an emerging identity crime with a steadily growing impact. Though difficult to estimate, SIF may have accounted for up to 20 percent of credit card financial losses, approximately US$6 billion, in 2017.7 Equifax, a leading consumer credit reporting agency, estimates that losses due to SIF were US$16.8 billion in 2017, compared to US$5 billion in 2014, representing an annual growth rate of approximately 50 percent.8

SIF is a growing problem for financial institutions. During the onboarding process, 95 percent of synthetic identities remain undetected. At the same time, the monetary losses from SIF are difficult to quantify, with estimates ranging between US$20 billion and US$40 billion.9

Social Media Platform Selection

Which social media platforms are suitable for SIF detection? In January 2023, the top-five consumer-oriented social media platforms, excluding messaging and location-based platforms, were Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Reddit and X, formerly Twitter (figure 1).10 LinkedIn is another popular platform, but it was not included in these rankings, likely because of its focus on business interactions. Messaging platforms are excluded as possible data sources for SIF detection because they aim to enable one-on-one interactions through text messages or audio or video calls. Also excluded are geographically concentrated social media platforms because they have limited utility outside their respective locations.

Source: Statista, “Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide by Number of Users, January 2023,” 2023, statista.com.

Republished with permission.

In contrast to RIF, SIF is easier to perpetrate but more challenging to use for criminal purposes.

To use a social media platform for SIF detection, it must have a well-developed social graph whereby users can connect with other users. In addition, to analyze user activity from a linguistic point of view, the platform must support rich and meaningful linguistic interactions through posts, comments and interactions.

With a focus on the banking and finance sector, the selected platform should represent users from the broadest possible range of age groups. Credit applications are not limited to a specific age group, and SIF can be committed across the age spectrum.

Finally, to apply these methods in the broadest possible context, social media platforms should represent users from different parts of the world rather than a limited number of countries.

As shown in figure 2, the two most suitable platforms for detecting SIF in online credit applications are Facebook and Twitter.

SIF Detection Using Social Media

The steps to detect SIF using social media are:

- Obtain and preprocess Facebook and Twitter data.

- Analyze Facebook and Twitter data to identify suspicious accounts using social media graph analysis (SMGA).

- Enter the values into the RSC to determine the level of risk and the need for human follow-up.

Obtain and Preprocess Social Media Data

When creating a fake online identity, also known as a sock puppet, establishing Facebook and Twitter accounts is an important step.).11 Therefore, when detecting synthetic identities, the existence of Facebook and Twitter accounts, the size of the user graphs and the extent of their activities, including comments, posts and language, should also be checked. Obtaining and processing Facebook and Twitter information can be done using a tool built on the KNIME (an open-source data science platform developed at the University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) Analytics Platform. In addition, to confirm whether a profile is real, user graph size and activities, the gender of the profile and its picture should be reviewed. Female profiles are more successful in instilling confidence and increase the risk of a synthetic identity.).12 The same applies to the absence of pictures across all social media accounts; these should be reviewed.).13

Social Media Graph Analysis

Graph analysis is a powerful analytical approach that focuses on extracting information from graphs. It is used for many real-world applications, such as brain networks, protein assembly and network vulnerability analysis. Among the many applications of graph analysis is SMGA.

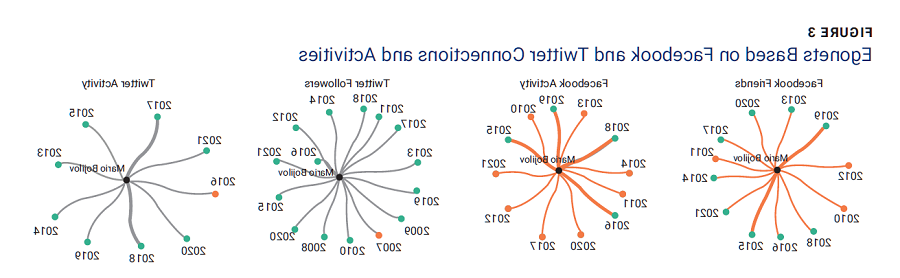

Social network analysis can be broadly divided into two categories: connections and their structure within a network and individual nodes, such as specific individuals or egonets. Egonets are networks based on a specific node, called the ego, and the immediate connections of that node, called its alters. A financial institution applying the proposed SIF detection approach would likely not have collected data on the connections of a credit applicant. In this situation, an egonet contains only the ego and no alters.

For SIF detection, the size of an egonet and the activities associated with it should be considered. The activities to be analyzed include commenting, post interactions and post sharing. These are the most common activities of Facebook users in terms of interactions between individuals. In the case of Twitter, the most common activities are tweeting and favoriting a tweet.

The criteria for identifying egonets that represent a SIF risk and should be brought to the attention of a human investigator are:

- Egonets with nodes numbering less than 25 percent of the average, based on the age of the ego

- Egonets in which 50 percent of the nodes have less than 25 percent of the average number of connections for the social media platform

- Egonets in which the ego has less than 25 percent of the average engagement activity

Figure 3 shows a set of egonets based on a sample of Facebook and Twitter connections and activities. The ego is the actual account and nodes, and line thickness re presents the amount of activity each year. The red-colored nodes indicate years when the values were below the threshold.

Risk Score Calculator

As mentioned, a vital component of this approach is the RSC. The RSC uses two inputs: the results of the SMGA and the results of a natural language processing (NLP) analysis. The RSC produces a score between 1 and 100, and it is a practical means by which a financial institution can screen credit applications and identify those requiring review by a loan officer. Low scores indicate a low probability of SIF and no need for a human review. A higher score indicates a higher probability of a synthetic identity, necessitating review by a bank officer.

Practical Implementation of a SIF Detection Process

This process has been implemented in KNIME. At present, KNIME has two product offerings:

- KNIME Analytics Platform, which is free

- KNIME Server, a commercial offering

A prototype of a SIF detection system built using KNIME Analytics is depicted in figure 4. It contains modules for reading configuration information and input data from relevant sources; performing the required analyses, such as social media (Facebook and Twitter) graph analysis; and providing visual output to bank officers and output to other enterprise systems through an application programming interface.

This prototype was evaluated by 36 audit and risk professionals. The demographics of the subject matter experts (SMEs) is shown in figure 5.

In the evaluation sessions, 82.9 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the methodology and the prototype provide an improvement in SIF detection compared to other analytical methods because they focus on activities that are difficult to forge (figure 6).

The RSC represents a promising opportunity for financial enterprises to screen credit applications more efficiently.

In addition, 94.3 percent of participants agreed or strongly agreed the methodology will provide value to their organization (figure 7).

Conclusion

By assessing the social media footprints of online credit applicants, SIF detection can be improved. The RSC represents a promising opportunity for financial enterprises to screen credit applications more efficiently. By incorporating a comprehensive set of inputs, including weights assigned by SMEs and data from Facebook and Twitter analyses, the RSC can be used to identify applications with a higher likelihood of SIF. This innovative approach enhances the credit screening process, streamlining operations and mitigating potential risk for financial institutions.

Endnotes

1 Herodotus, The History of Herodotus, The Internet Classics Archive, 440 B.C., http://classics.mit.edu/Herodotus/history.3.iii.html

2 Stern, G.; “Imposters in the Ancient World,” p. 16–20, http://www.academia.edu/36132713/Imposters_in_the_Ancient_World

3 The Balance, “A Brief History of Identity Theft,” 2020

4 Phua, C.; K. Smith-Miles; V. Cheng-Siong Lee; R. Gayler; “Resilient Identity Crime Detection,” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, vol. 2, iss. 3, 2012, p. 533–546

5 Kshirsagar, A.; L. Dole; “A Review on Data Mining Methods for Identity Crime Detection,” International Journal of Electrical, Electronics and Computer Systems, vol. 2, iss. 1, 2014

6 Ibid.

7 Jooss, R.; “Synthetic ID Fraud: It’s Very Real,” Credit Union National Association, 13 November 2018, http://news.cuna.org/articles/115148-synthetic-id-fraud-its-very-real

8 Equifax, “The Stark Reality of Synthetic ID Fraud in the Communications, Energy and Digital Media Industries,” 2018, http://www.equifax.com/resource/-/asset/white-paper/stark-reality-synthetic-id-fraud/

9 Simons, T.; “Trends in Synthetic Identity Fraud,” Thomson Reuters, 2023, http://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/insights/articles/trends-in-synthetic-identity-fraud

10 Statista, “Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide by Number of Users, January 2023,” http://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

11 Bardin, J.; “Open-Source Intelligence by Jeff Bardin,” 2020, http://privacy-pc.com/articles/open-source-intelligence-by-jeff-bardin.html

12 Bertram, S.; The Tao of Open Source Intelligence, 1st Edition, IT Governance Publishing, UK, 2015

13 Ibid.

MARIO BOJILOV | PH.D, CISA

Has been a professional in the field of data analytics and business improvement since 1994 and is a lecturer in accounting information systems (IS), IS control and governance, enterprise resource planning, and systems analysis and design. His expertise extends to the areas of finance, digital transformation, digital risk and IS audit, including significant involvement in IS governance and audit. He served as president of the ISACA® Brisbane (Australia) Chapter and was a member of the ISACA International External Advocacy Committee. In 2004, Bojilov founded MBS Worldwide, where he is chief executive officer. Government entities, private organizations and higher education institutions have benefited from the business improvement, performance monitoring and technology governance solutions provided by MBS Worldwide and the impactful in-house training programs delivered by MBS Academy.

KISHORE SINGH | PH.D

Is a senior lecturer in accounting data analytics at Central Queensland University (Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia). Kishore is also a certified fraud examiner and has an excellent track record in IT security, network and systems management, and software development. His research covers continuous auditing and monitoring, data visualization, forensic accounting and fraud detection in enterprise systems. He has published several articles on topics related to these areas. Kishore spent several years researching and developing methods and procedures for fraud detection in SAP enterprise systems. He has also consulted for large local and international enterprises in the areas of forensic analytics and antimoney laundering.

PETER BEST

Is adjunct professor in accounting at Central Queensland University (Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia). He formerly held the position of professor and head of the College of Business. He has also held positions at Flinders University (Adelaide, South Australia, Australia), Griffith University (Nathan, Queensland, Australia), Queensland University of Technology (QUT) (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia), University of Adelaide (Adelaide, South Australia, Australia), University of Newcastle, Australia (Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia) and University of Southern Queensland (Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia). Best has qualifications in accounting, operations research and IT. His teaching, research and consulting interests include business intelligence and data mining, enterprise systems (SAP), information systems security and audit, sustainability reporting and assurance, automated fraud detection, and data visualization.